Opposition to the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline has focused on the absence of a public need for the pipeline. Dr. Dennis Witmer has supplied evidence refuting the asserted public need for Atlantic Sunrise. He also testified to the absence of a public need for the Sunoco Pipeline Mariner East 2 pipeline. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission continues to evaluate the Atlantic Sunrise proposal. Faherty Law Firm represents many property owners threatened by the Atlantic Sunrise proposal.

Battle’s new front: pipelines

As low prices for natural gas cause drillers to pull up stakes, companies are building conduits to move fuels to ports. Midstate residents are trying to stop the projects.

Written by: Colin Deppen | Patriot News

The energy boom of the last decade has, in the last year, grown eerily silent.

The drilling of new wells has slowed with the fuel supply outpacing demand and low prices dogging the market.

In response, drillers have moved out of Pennsylvania towns, leaving behind empty rental homes and ancillary businesses that now face their own uncertain futures.

But existing Marcellus Shale wells, many drilled in the last eight years, continue to produce huge amounts of natural gas, unfazed by any slowdown. In many cases that production is a legal requirement of the land leases that made such wells possible, prompting the energy companies that have for years been preoccupied with inking new leases and pulling more gas from the ground to focus on what to do with the gas flowing to the surface.

This is the legacy of the Shale boom and much of the reason for the energy industry’s wholesale push toward pipeline development, which was at the center of a heated public debate over industry encroachment, property owner rights and the use of eminent domain in securing private land for “the public good.” The stage for this conflict has shifted from the primarily wooded outposts of the northern tier and southwest to more-populous communities on the pipelines’ path to eastern and southern hubs.

In places such as Lancaster County, home of about 500,000 residents, landowners oppose Williams Co.’s planned Atlantic Sunrise pipeline project, fearing the $3 billion, 10-county project’s impact on property values, quality of life and livelihoods.

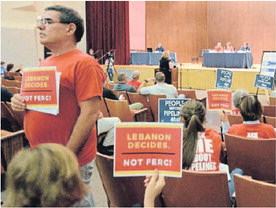

Many raised these concerns in a public meeting Monday in Lancaster County as the company maintains that the project minimizes human encounters and environmental harm as it promises economic gains. Central to the discussion is the use of eminent domain in securing routes for projects to feed fossil fuels toward the sea and markets across the globe.

That meeting and one Tuesday in Lebanon County, both hosted by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to gather public input, included protesters on both sides of the issue involving the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline.

Recognized reasons for using eminent domain have included highways, roads, schools, public buildings, airports and pipelines. But now, with domestic energy and natural gas production shattering records and pipeline projects taking shape across the country, eminent domain and pipeline battles are becoming par for the course.

Guidelines for formal residential challenges remain elusive and the results far from predictable, experts say.

Opponents, meanwhile, blame a lack of legal precedent and what they see as the incestuous involvement of regulators rigging the system in the industry’s favor. The industry has responded by saying it is simply exercising its legal right to do business under the law.

Fights yet to come

Perhaps the most notable of these challenges took place in 2015 with more than 100 landowners in Nebraska going to court to oppose TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline project in a case that forced the company to go back to the drawing board. TransCanada had used eminent domain to gain access to properties in other states, but Nebraska holdouts forced the issue in court.

President Barack Obama rejected the pipeline plan after seven years of review, leaving the company to look for new means of shipping tar sands oil from Alberta to the Gulf Coast. The company later filed suit against the president for his rejection of the project.

Smaller-scale pipeline disputes and eminent-domain battles continue to crop up across the nation, including in Pennsylvania. Central to the issue is whether pipelines serve the public interest.

Dennis Whitmer, an energy analyst and Lancaster County native, said the industry maintains they do, but with prices so low and domestic consumption declining, the case in favor of pipelines as a public benefit is getting harder to prove.

“The existing domestic market is adequately served by the existing pipeline infrastructure,” Whitmer said. He maintains that the Atlantic Sunrise project in Pennsylvania is not needed to serve any domestic market.

Beyond the U.S., he said, industry hopes are pinned on the global market to make up for falling domestic-energy consumption here. Whitmer calls this a pipe dream, one that seems less and less likely, at least in the short-term.

Pipeline critics say the industry enjoys a far lower bur- den of proof than members of the public.

“We have a hard time getting traction sometimes because the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission doesn’t require these companies to do much in the way of showing that there is an actual need in the marketplace, or on the part of the public, for the product being shipped through the pipeline,” said Augusta Wilson, staff attorney with the Clean Air Council in Philadelphia, an opponent of pipeline projects including the Atlantic Sunrise.

FERC often serves as the first stop for pipeline challenges, particularly those involving eminent domain claims, and has been called a rubber-stamping agency by critics.

“The big gorilla in the way is FERC, and the FERC process excludes and overrides a lot of other processes,” Alex Bomstein, a senior litigation attorney with the Clean Air Council, said in March.

FERC has never rejected a pipeline plan.

Bomstein said there have been recent victories for Pennsylvania’s pipeline opponents, including getting a Philadelphia County Court to allow a challenge to Sunoco’s use of eminent domain for its Mariner East 2 pipeline project, despite the company’s objections.

Strong opposition

In Lancaster County, about 40 property owners continue to resist the Atlantic Sunrise project, said Mark Clatterbuck of the Lancaster Against Pipe- lines protest group.

In Lebanon County, which is to be bisected for 27 miles north to south by the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline, Ann Pinca of the Lebanon Pipeline Awareness group said there were 30 to 35 holdouts as of March. Meanwhile, 60 to 70 county residents had signed easements for the project at that time.

“On the one hand, you have a public that is much more aware now of what is being proposed for their neighborhoods and what the consequences would be,” Bomstein said. “And on the other hand, you have pipeline companies doing ever more outrageous things because they got away with them and who are now pushing up against the limits of what society will tolerate and allow.” He added, “Our most successful fights are happening now and are yet to come.”

Difficult cases to win

Courts likely will weigh a pipeline’s public and private benefits and whether eminent-domain power for its builders is appropriate. Much of this likely will happen in response to individual legal challenges, experts say.

In Iowa in January, an appeals court ruled that a northeastern Iowa farmer could pursue a breach-of-contract lawsuit against a natural gas pipeline company and seek damages for decreased crop productivity on the ground above a pipeline. Suits also have been filed this year regarding a pipeline leak in California and by Wisconsin residents demanding that a pipeline outfit obtain insurance against their losses.

In Houston last year, an appeals court decided that a carbon dioxide pipeline project did not have the automatic right to eminent-domain status and that the company behind it had to prove that the project would benefit the public. The Texas Supreme Court has agreed to rehear the case.

The tide of public opinion has turned against the industry and pipeline projects since Congress’ 1938 endorsement. Experts say that tide is unlikely to reverse anytime soon as pipeline projects grow bigger and more plentiful, ensuring that more Americans stand to be affected and inspired to take action.

At the same time, pipeline companies file suit to assert their rights and counter what they see as unfair regulatory hurdles. The results of such legal actions are helping to shape the future for an industry in need of new infrastructure and cash as well as residents whose land stands between those companies and their bottom lines or larger energy markets.

In 2006, changes to the Pennsylvania Eminent Domain Code limited the uses that qualify as valid public use. Pipelines, however, continue to meet that definition.

“The problem is,” Whitmer said, “especially if you’re going to fight eminent domain, you need a good lawyer, and the other side has essentially an unlimited amount of money for legal battles.” He added, “My biggest hope for preventing construction of the Atlantic Sunrise project is not a court case denying it but rather that people and the industry finally coming to their senses and realize there is no need for a pipeline like this.”

Photo caption: A pipeline protester turns his back on pro-pipeline speakers at a public hearing for the Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline Project at Lebanon Valley College on Tuesday.

Photo: Colin Deppen, PennLive